Rumblings

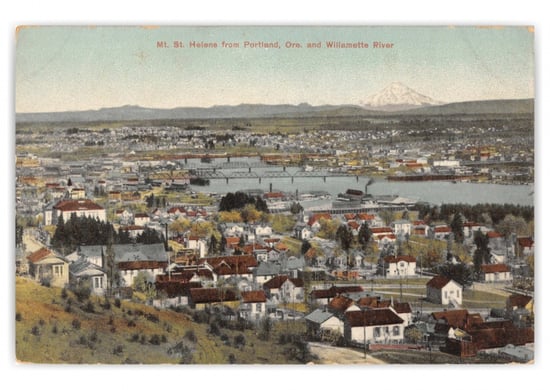

Towering thousands of feet above the sparsely populated southern Washington forest stood Mount St. Helens. Located 52 miles northeast of Portland, Oregon, and 98 miles south of Seattle, the volcano was considered dormant with few in the region believing the mountain to be a threat.

However, on the clear, springtime morning of May 18, 1980, everything changed.  The people of the Klickitat tribe knew the mountain as “Louwala-Clough”, or “smoking/fire mountain”. During European exploration of the region, George Vancouver named it after a British diplomat, the 1st Baron St. Helens. Later, the peak became known colloquially as the “Mount Fuji of America” due to its conical shape, strikingly similar in form to the Japanese mountain.1

The people of the Klickitat tribe knew the mountain as “Louwala-Clough”, or “smoking/fire mountain”. During European exploration of the region, George Vancouver named it after a British diplomat, the 1st Baron St. Helens. Later, the peak became known colloquially as the “Mount Fuji of America” due to its conical shape, strikingly similar in form to the Japanese mountain.1

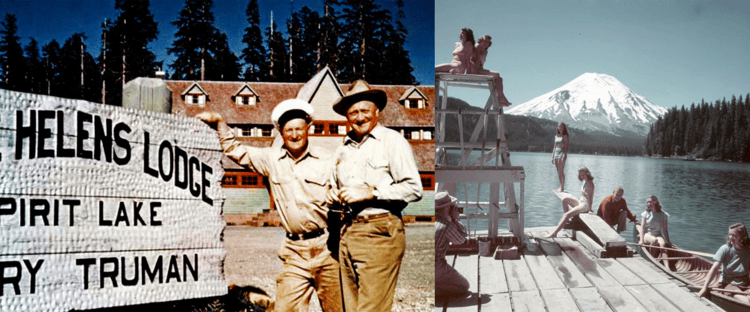

The area around the mountain, most notably Spirit Lake, became a recreational hotspot during the early and middle part of the 20th century. People flocked to the lake and its surroundings to go boating, swimming, and camping in the summer, while the winter offered plenty of skiing on the slopes of the mountain itself. All this would come to an abrupt halt in the spring of 1980.

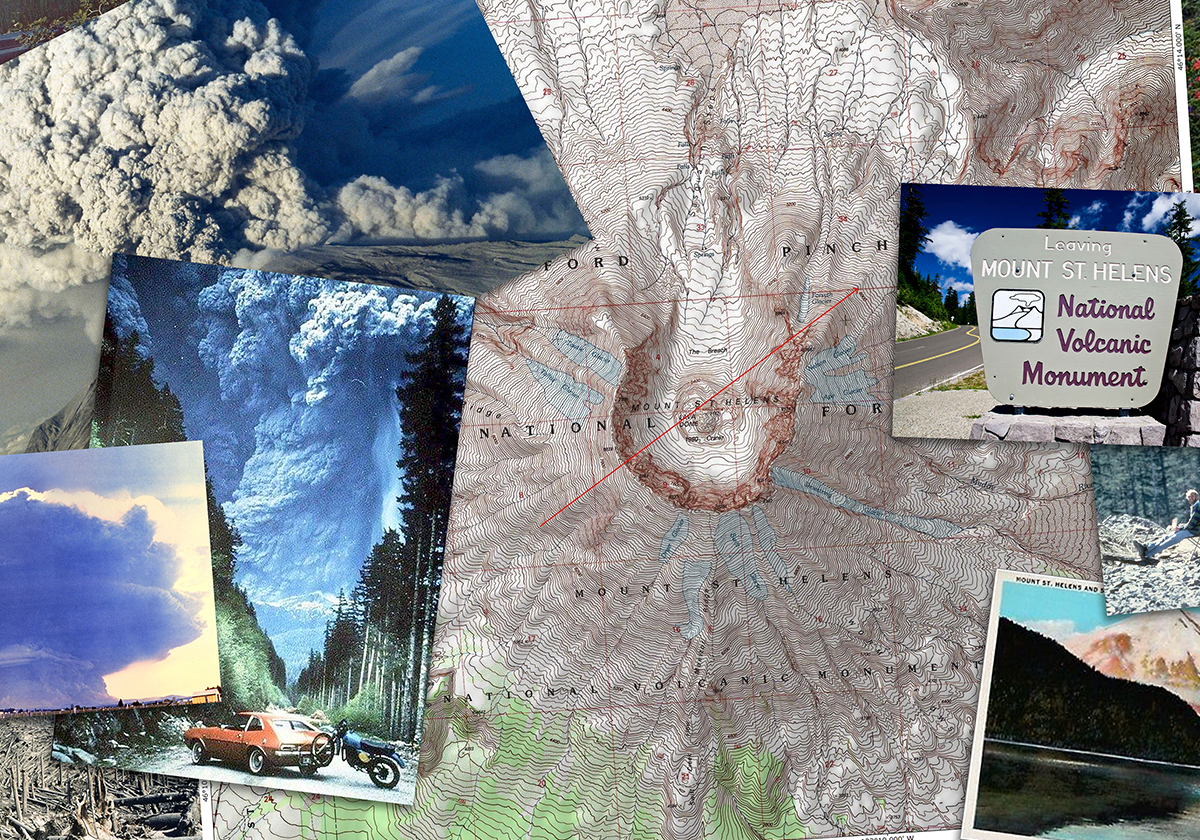

Before the eruption, the Mount St. Helens area played host to

vacationing pleasure-seekers year-round.

Related:

To Educate Customers About Earthquake Risk,

Look Beyond Fault Lines

For two months leading up to that notorious May morning, the mountain had begun to rumble.2

On March 16, thousands of earthquakes took place around the peak – nearly a week later, a powerful earthquake sparked several snow avalanches.

On March 27, the mountain emitted its first visible sign of an impending eruption: a 6,000-foot-high ash cloud billowed into the sky. For the following weeks, ash continued to spit forth from the volcano.

On May 7, the mountain began to move and shift, growing outwards at a rate of five feet per day as magma oozed up from the depths of the earth.

During the months leading up to the final explosion, volcanologists flocked to the scene. Though each brought a unique perspective to the unfolding events, they were all certain of one thing: a massive eruption was inevitable.

The eruption

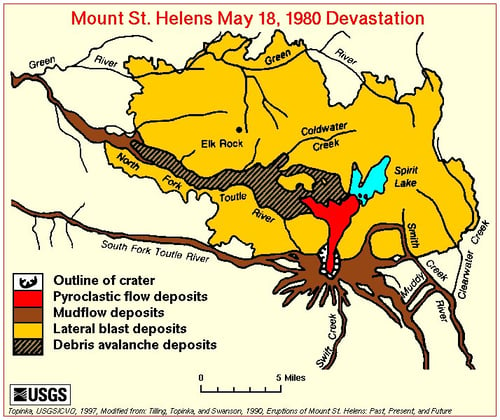

At 8:32 am on May 18, a 5.1 magnitude earthquake occurred beneath Mount St. Helens, triggering the largest landslide in recorded history.3 As the north face of the mountain sluffed away, a slurry of partially molten rock exploded outwards. A cloud of superheated ash and stone (clocking in at over 660°F) shot outwards at speeds of at least 300MPH, depositing material in a 230-square-mile area north of the volcano.4

In conjunction with this initial blast, mudflows, pyroclastic flows, lahars, and floods buried the valleys surrounding the mountain in a sludge composed of earth and debris while a massive 16-mile-high column of ash streamed skyward.

While the immediate effects of the volcano devastated the surrounding region, what is best remembered in the collective memory were the apocalyptic ashfalls.

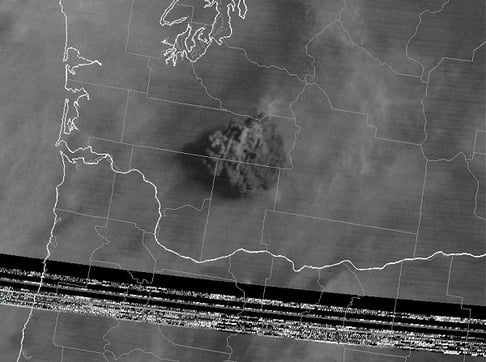

In Spokane, 250 miles away from the volcano itself, the sun was blotted out, leaving the region in temporary darkness. Further east, ash accumulations were reported in Denver, Minnesota, Oklahoma, and Yellowstone National Park. All told, the main eruption of Mount St. Helens produced 540,000,000 tons of ash that spread out across an area of 22,000 square miles.5

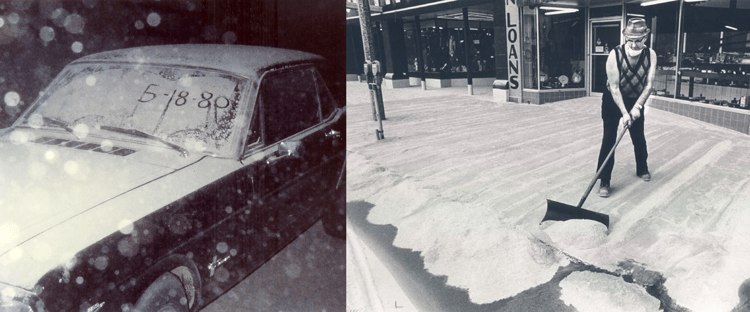

Cities in Washington like Spokane and Yakima saw massive amounts of

ash accumulation following the eruption.

Related:

An Agent's Guide to Earthquake Risk

The eruption released 24 megatons of thermal energy – 7 megatons during the initial blast and 17 megatons through the subsequent release of heat. This eruption was 1,600 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.6

Damage

The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens was the most destructive volcanic eruption in the history of the contiguous United States, causing numerous deaths and destroying large swathes of public and private infrastructure in the region.

As a result of the initial blast, ashfall, and subsequent lahars, 57 people lost their lives. The majority of deaths occurred as a result of asphyxiation, trauma, and thermal injuries, however, several deaths were caused due to poor visibility and two people died of heart attacks while shoveling ash.7

The scope of property damage and economic impact was extensive:

- 200 homes were destroyed

- 47 bridges were destroyed

- 185 miles of highway were destroyed

- 15 miles of railways were destroyed

- 30 logging trucks, 22 transport vehicles, and 39 railcars were damaged or destroyed

- Over 4 billion board feet of timber were damaged or destroyed (enough to build roughly 300,000 homes)

- Many agricultural crops (wheat, apples, potatoes, and alfalfa) were destroyed

Adjusted for inflation, the total cost of damage caused by the eruption, determined by the International Trade Commission, came out to be roughly $3.4 billion. Other indirect and intangible costs of the eruption also occurred, including skyrocketing unemployment in the region, a severe downturn in tourism, and increased rates of stress and other mental health problems.

What can we learn?

It is amazing to think how, practically overnight, an event like the eruption of Mount St. Helens can bring about such dire human and economic consequences. The relatively isolated geographic position of Mount St. Helens undoubtedly limited the potential for more devastating results. Just imagine if this volcano was in a region with a higher population density or was closer to a major metropolitan center.

Across the United States, there are populations that exist within proximity to volcanoes - from Mount Rainier, South Sister, and Mount Hood in the Pacific Northwest to Mount Shasta in California and Mauna Loa in Hawaii.8 While outright eruptions of the scale seen at Mount St. Helens in 1980 are rare, the increased potential for earthquakes and resultant lahars and tsunamis is important to be aware of.

Being able to geographically visualize earthquake, lahar, and tsunami risk can help you manage exposure concentration effectively and ensure that your customers have the coverage they need. At BuildingMetrix, we've developed tools to help with these visualizations and allow you to take control of and power future sales.

If you'd like to learn more, contact our risk data experts.

[1] McGill University, https://www.cs.mcgill.ca/~rwest/wikispeedia/wpcd/wp/m/Mount_St._Helens.htm

[2] History, https://www.history.com/topics/natural-disasters-and-environment/mount-st-helens

[3] Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1980_eruption_of_Mount_St._Helens

[4] Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/place/Mount-Saint-Helens

[6] USGS, https://web.archive.org/web/20130512162409/http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2000/fs036-00/

[7] Oregon State, https://volcano.oregonstate.edu/faq/what-were-effects-people-when-mt-st-helens-erupted

[8] Daily Mail, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-5746231/Do-live-near-volcano-blow-Interactive-map-reveals-cities-risk.html